"efficient (adj.)

1. (of a system or machine) achieving maximum productivity with minimum wasted effort or expense.

2. (of a person) working in a well-organized and competent way."

*(Oxford Dictionaries)*

"Efficiency is a measurable concept that can be determined by determining the ratio of useful output to total input. It minimizes the waste of resources such as physical materials, energy and time, while successfully achieving the desired output."

*(Investopedia)*

From the latin verb efficiō –meaning to execute, to accomplish– the modern sense of the word 'efficient', according to the same Oxford Dictionaries from where I extracted the opening quote of this text, only came into existence in the late 18th century, roughly around the same time as the Industrial Revolution was entering upon.

Taylorism, a theory of labour developed from the 1880s onwards by Frederick Winslow Taylor –himself one of the main influences within the ‘Efficiency Movement'– was committed to the quest of achieving the perfect ratio of "useful output to total input" to such an extent that some of its proponents went to the point of collapsing the person with the machine as a desired outcome. One such example is Alexei Gastev, founder of the Central Institute of Labour in the Soviet Union, advocate of the "principle of mechanization" and the "biological automatization" of workers (The Charnel House, 2011).

Also known as the scientific management of labor, Taylor’s brainchild consisted of an array of techniques for disciplining workers’ bodies into becoming efficient productive machines. Motion studies, calculation and metrics would produce the knowledge necessary to inform the training of workers and the rational allocation of human resources. Nikolas Rose understands this process as the first of many attempts to provide management with rational legitimacy. Fabricating compliance was thus essential for preventing conflicts between worker and employer. The perfect Taylorist worker would thus be a docile body, as compliant and sturdy as the steam engine (Gregory, Hendry, Watts, Young, 2017).

But this reductive vision of the worker would not last forever. In "Governing the Soul – The Shaping of the Private Self", specifically within the chapter "The Productive Subject", Nikolas Roses maps the developments which allowed for these theories, if not to subside, to evolve. When World War I struck and demands grew heavier on workers’ bodies, it became clear that the worker-machine had limitations and was bound to fatigue and other health-related issues. According to Rose, this allowed for a series of interventions that would gradually shift the conception of the worker as mere physiological apparatus. In 1921 C.S. Myers established the National Institute of Industrial Psychology in the United Kingdom, marking a new era where the psychology of the worker became a crucial way of re-conceptualizing industrial efficiency and peaceful continuation.

In the United States, too, the ways of conceiving the working body shifted similarly. However, whereas in the United Kingdom the focus was on individual differences, in the United States the problem was conceptualized in terms of human relations within the group. Overall, workers’ subjectivity “had emerged as a new domain for management” (Rose 1989), which set itself as a neutral, independent authority that would act as a middle man between worker and employer, smoothing out the frictions that might arise between them. Moreover, the enmeshment of the worker’s subjectivity in the life of the company was to create a sense of belonging and common, shared goals, stimulating a renewed personal investment in the advancement of the company’s interests.

Pinning rightful work discontent caused by systemic inequality down to maladjustment and pathology, this managerial approach to workers' subjectivity obscures workers’ exploitation in layers of scientific authority, centering the problem on the self and its immediate conditions. In turn, this promotes an internalization and individualization of the problem, thus obfuscating the larger infrastructure/superstructure complex engendering workers’ collective exploitation. These thoughts seem to be echoed by many critics who claim that these interventions did nothing to solve basic inequalities . While Rose sees much truth in these analyses, and indeed links these managerial efforts with a hope to weaken trade unionism, he warns against regarding these discourses as purely ideological as to do so would imply that the knowledge involved in the management of the workers' psyche is false.

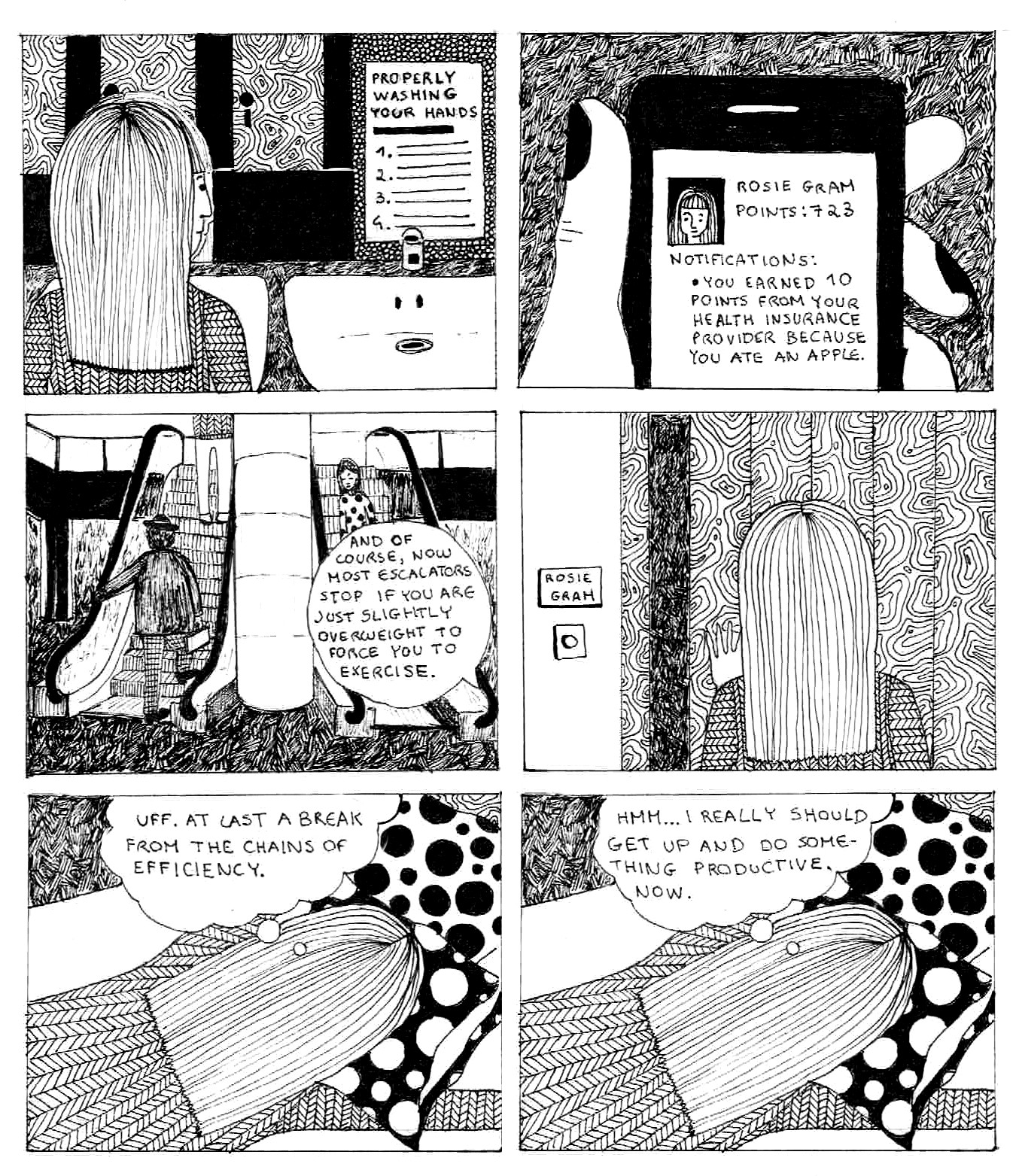

According to Michel Foucault, the preoccupation with the wellbeing of the general population for the purposes of a strong and healthy state dates back to the 18th century Western societies. Such an endeavor requires not only large amounts of data, but also that every individual participates in their own governance. Governmentality thus refers to structural entanglement of self-government with the government of a state (Lorey 2006). In her reading of Foucault’s biopolitics within the context of self-precarization, Isabell Lorey explores how ideas of freedom and autonomy are constituted in Western capitalist societies. What does it mean to 'choose' precarity within the context of neoliberal governmentality?

From Foucault’s History of Sexuality, Lorey extracts the fundamental notion that the modern Western subject must gradually learn a relationship with themselves. Here, the self emerges as something to be shaped and developed. This development is modeled on the concept of "normal" (e.g. white, male, bourgeois, national, etc), which Lorey identifies with the hegemonic; this concept is infused with the sense of authenticity, thus obscuring the effect of power on the construction of the self. Whilst traditionally those who did not fit the norm were made precarious, Lorey posits that, in neoliberalism, precarization is transformed from an exception into a hegemonic, normalized function. Self-precarization, thus, serves the needs of economical and governmental power whilst at the same time beclouding its role.

Both for forced and self-chosen precarization the narrative is one of creating one's own opportunities and devising one’s own means of economical success – in short, becoming an entrepreneur. This state imposed narrative is characterized by a shift of responsibility, letting the governed subject shoulder the consequences, as well as the blame, for their failures, obscuring decisive factors which might hinder equal access to opportunities such as class, gender, race, neurological differences, etc.

"In a neoliberal context they [the self-precarious] are exploitable to such an extreme that the state presents them as role models." (Lorey 2006)

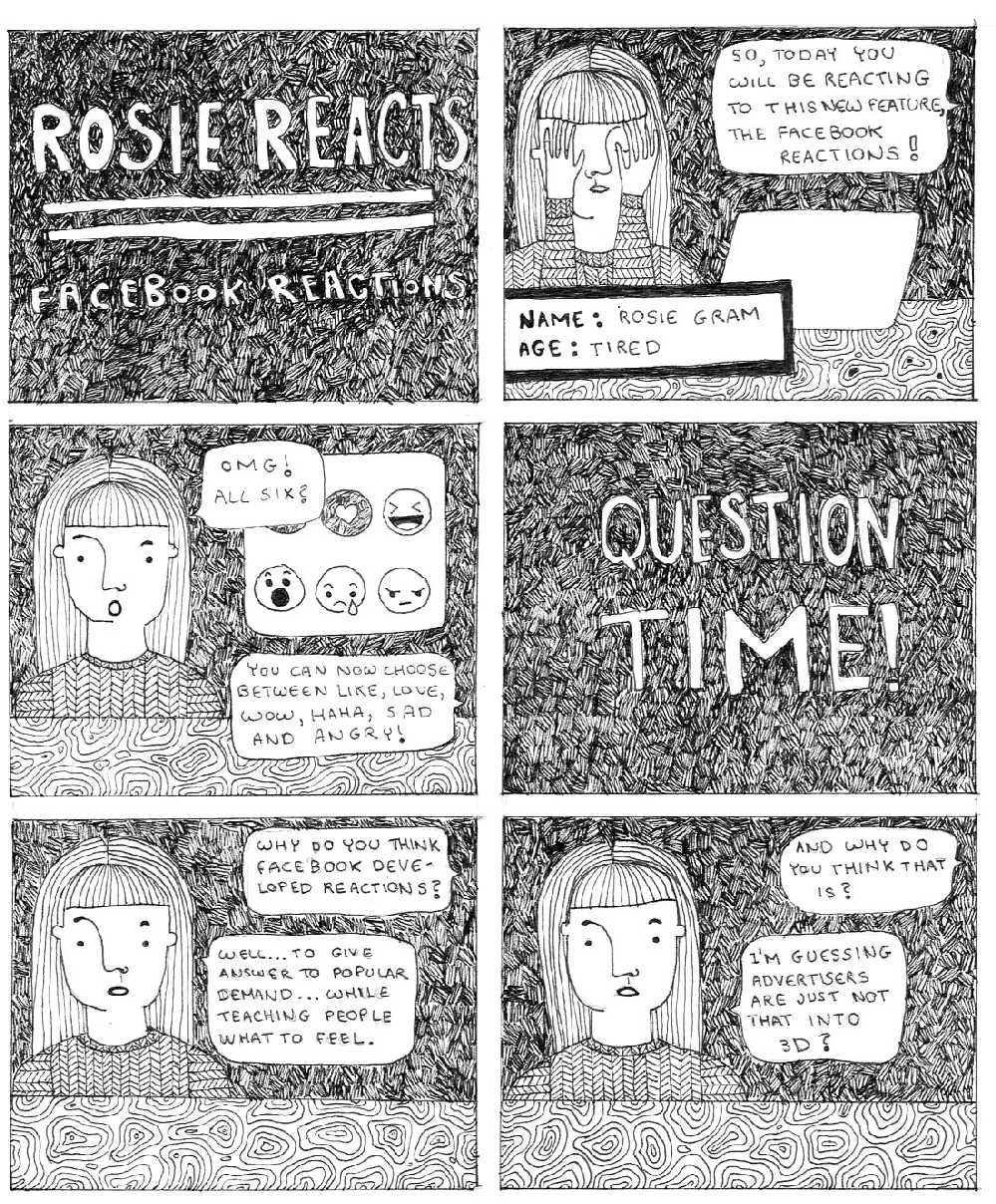

This role model, the normalized identity which corresponds to the hegemonic, is that of a tireless individual who is alert and always ready, a force of nature with a strong presence that is mostly white, often male, charming, creative and gregarious. The normal subject is someone with the ability to, first and foremost, sell themselves, whose social skills are well tuned and whose energy comes from connecting with others. A force to be reckoned with, this well of virtues is resilient, organized, flexible, efficient... the list goes on and on. Within the neoliberal environment, where precarious bodies need to constantly prove themselves economically viable, being visible can also be decisive –every event is an opportunity to trade in social capital, every party might decide whether economical survival will be possible for the next couple of months. Where everyone is an entrepreneur, everyone can become your next investor. Being seen as productive often becomes more important than production itself.

Lorey identifies self-precarization with feelings of fear, loss of control, insecurity, as well with a redefinition of the boundaries between work and leisure. Always having to be "on" and prove yourself constantly to others is a taxing project on everyone forced to exist under such conditions – even for those who fit the ‘job’ description almost to a tee. We can imagine it is even more so for the precarious within the precarized population –the neurodiverse, people of colour, female, transexual, introverted, anxious, etc. For them, fitting in always involves some degree of self-mutilation and adaptation. As an example, a simple internet search for "introvert" returns several links to articles about the hidden power of the introvert, the wonderful mythical creature with a rich inner world that can become a great leader if his/her powers are respected and correctly harnessed. Likewise, several articles praise the value of having a person on the Autism Spectrum on your work team. This stereotyped and mystified narrative, besides being unhelpful and assuming some degree of advantage, immediately places an inordinate amount of pressure on these people to make up for their deviance to the norm with the "unique" attributes they are famed to have. Acceptance comes at the price of constant performance of an attributed set of traits, qualities and strengths. Much of the mainstream discourse in this arena condescendingly engulfs all diversity into a productive body: individual differences are taken into account as long as they are coherent with their official portrait and in so far as they can be made exploitable by capital.

Coherence might just be a key concept to retain and explore further. Lorey underlines its importance as a fundamental of modern sovereignty – self-governing depends on an imagined coherence and wholeness that shapes itself on the mold of "normality". Likewise, in order to be made productive, "abnormality" must be absorbed into a perfectly defined identity that is thus easier to govern. If constructing one’s identity boils down to attaining some sort of perceived coherence, when this requirement fails the individual becomes susceptible to what some psychologists call ‘ontological insecurity’. Ontological insecurity, which R.D. Laing defines as the lack of an overarching "sense of personal consistency and cohesiveness", is a postmodern condition as Rob Horning maintains in his "Sick of Myself".

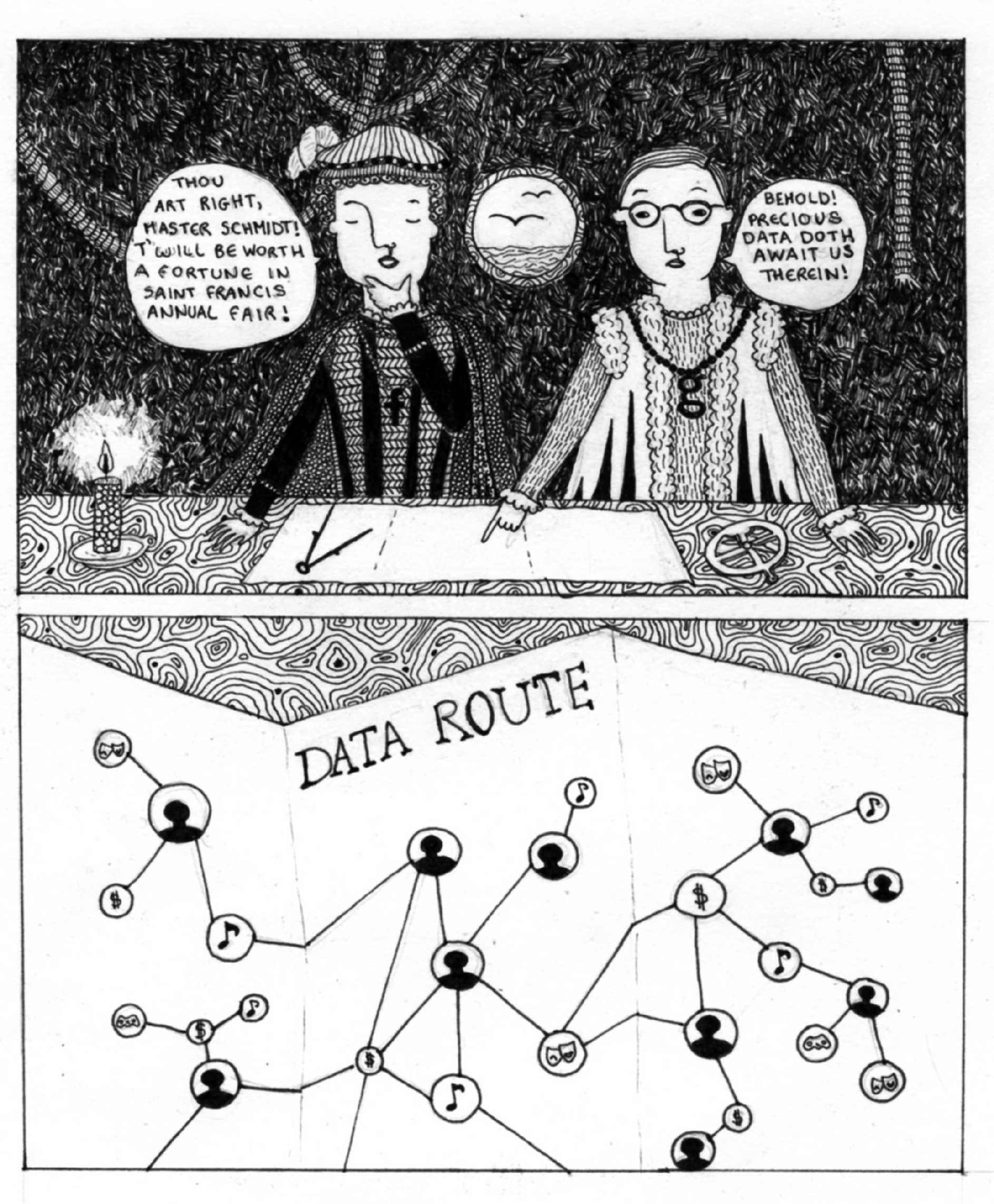

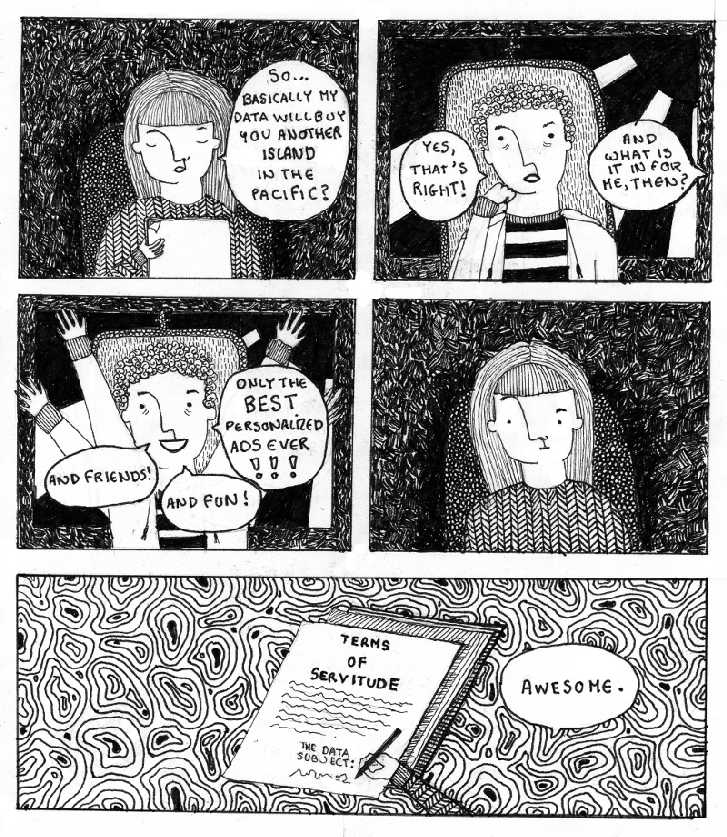

Where everyone is concerned with becoming themselves, with self-realization, self-improvement, and other self-alienating techniques, attention shifts away from community building, organization and strengthening of solidarity bonds between individuals. For all of its promotion of networking and social interaction, normalized precarious identity, where everyone is an entrepreneur of the self, is paradoxically isolating. In this scenario, human relations are not conceived as bonds of solidarity and shared struggles, but established as a means to achieve an end –they’re the promise of future financial gratification. Evoking the image of the social graph (the graphical representation of relationships between everybody and everything on the internet), Yuk Hui and Harry Halpin underline that the visualization of social networks as nodes and links "reinforces the philosophical assumption that social relations always exist in a reified manner as 'links' between one atomic unit and another" (Hui and Halpin, 2013). Presiding not only over our online, but also over our offline lives, these atomized representations challenge the possibilities for collectivized counterbehaviour which, Lorey states, is currently missing.

Could a radical refusal of coherence be the basis to start constructing such collectivized counterbehaviour? Could idiosyncrasy be part of the answer to Lorey’s question as to what, within neoliberalism, functions as deviant and cannot be exploited in this way? An inconsistent, incoherent and idiosyncratic mass that refuses their deviance to the hegemonic norm be made compliant with the requirements of the economical system. Organization on the basis of acceptance as opposed to adaptation, where society cares for the individual even if it can’t commodify its "unique" traits.

If we are too difficult to predict we become, in the best possible scenario, dangerous. In the worst possible scenario, of little or no use to the market. Unity, accountability, predictability – these are the most prized traits in a governable subject. Can we ever refuse them?

Bibliography

The Charnel House (2011) The ultra-Taylorist Soviet utopianism of Aleksei Gastev.[Online]

Rose, N. (1989) Governing the Soul: the Shaping of the Private Self. Second Edition. London: Free Association Books.

Llorey, I. (2006) Governmentality and Self-Precarization: On the normalization of cultural producers. [Online] Available at: http://eipcp.net/transversal/1106/lorey/en

Gregory, K., Hendry, K., Watts, J., Young, D. (2017) Selfwork: How fitness technologies turn the body into an investment property. [Online]. Real Life Mag. Available at: https://reallifemag.com/selfwork/

Horning, R.(2017) Sick of Myself: Algorithmic identity is a means of control and consolation. [Online] Real Life Mag. Available at: https://reallifemag.com/sick-of-myself/