Welcome to the 11th issue of the Pervasive Labour Union zine. This special issue is marked by a substantial name change motivated both by the refusal to obscure the material dimensions of digital labor and by the determination to scrutinize its pervasiveness. Thus, the zine will engage with work's ability to invade, colonize and commodify the realms of public space, leisure, social bonding, affect, intellect etc. More information on the name change can be found in the previous issue.1

The strategic colonization and commodification of relationships with others and with the self is one of the predominant features of the ‘entreprecariat’ , which is the focus of this issue. The term emerged from the realization that, while an array of diverse forms of precarity (financial, professional, and even existential) is becoming the norm for a growing number of people, so it is the necessity to tackle them entrepreneurially. As witnessed by the emergence of terms like ‘entrepreneurism’, individuals as well as institutions are increasingly urged to think of themselves as brands, companies or startups. Against a backdrop characterized by relentless destabilization, entrepreneurship, the practice of starting and managing a business through risk, turns into entrepreneurialism, a universal doctrine with its own dogmas, martyrs and plans of salvation.

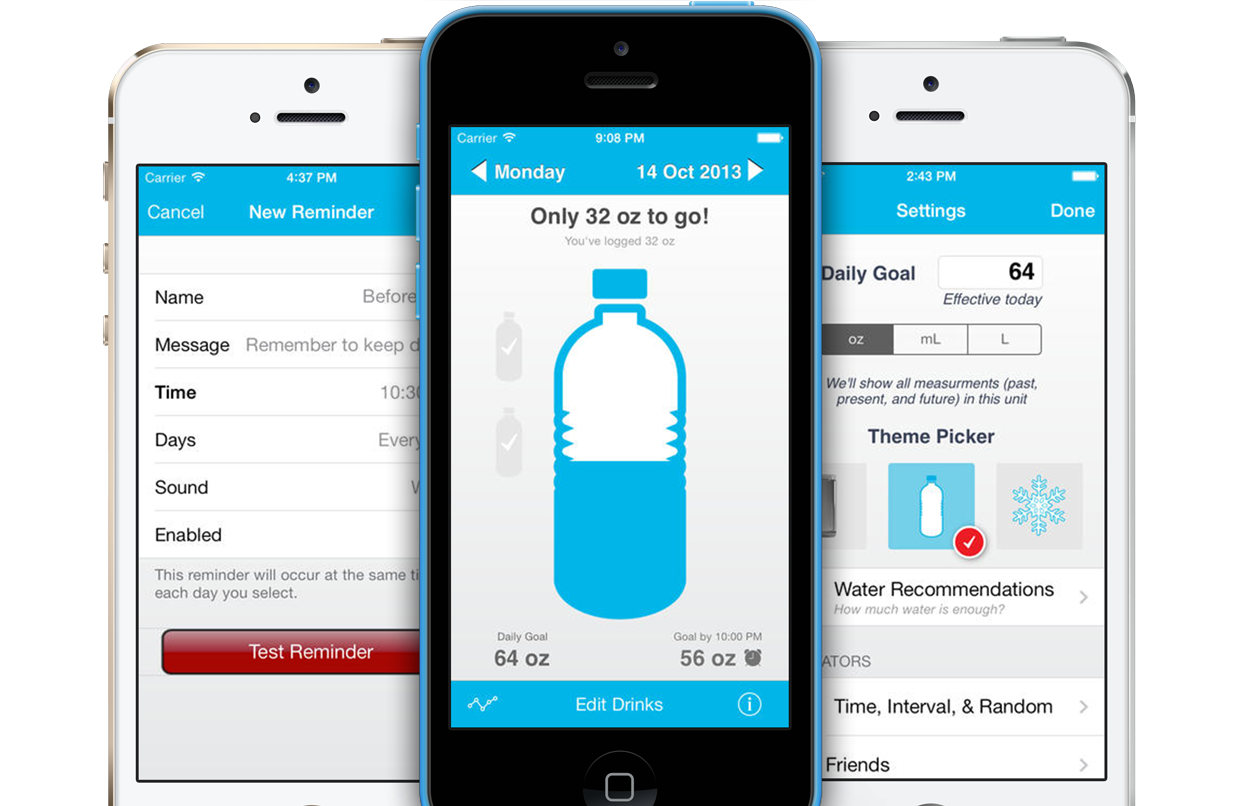

In this special issue we wanted to explore the multiple ways in which entrepreneurial ideas, models and approaches relate to current perceptions of precarity. We had numerous questions in mind, among them: What happens when the rhetoric of technological innovation meets career-oriented self-help literature? How does the cult of Elon Musk or Marissa Mayer and their unlikely sleeping patterns perturb narratives of self-affirmation and professional lifestyles? When does the conscious adoption of the entrepreneurial attitude turn into a mandate? How to articulate the threshold between passion and self-exploitation? What is the role played by technology? How do productivity tools, social media and wellbeing apps transform or intensify the professional government of the self? Finally, is it possible to combine the entrepreneurialist drive with collective expressions of precarity? Or should insecurity itself become a paradoxically stable ground on which to build social cohesion?

The zine includes 22 (!!) contributions coming from different contexts, both in terms of geography (Netherlands, Belarus, US, Italy, just to mention a few) and practice (academic writing, fiction, visual arts and even videogame review). Several contributions tackle the emotional, relational and psychological dimension of entreprecarity, focusing on the micro- and macro-aggressions that take place in work-related environments (Evening Class); the economic exploitation of stress (Katriona Beales); the ennui and caffeinated solitude of the cognitive worker (Phil N/A); the awkwardness of the work-centric first encounter with strangers (François Girard-Meunier), the psychological toll of a not-so-fictional bot-mediated remote freelancing soliloquy (Juliette Cezzar).

Some texts scrutinize the startup world and the field of tech entrepreneurship, specifically the IT universe of Belarus (eeefff); the somehow dadaist newspeak emerging from the innovation and disruption zeitgeist (Olivier Fournout); the eulogy of sacrifice and martyrdom (Priya Prabhakar); the compulsion to come up with business ideas (Melissa Mesku); the self-help propaganda deriving from the mythological lives of tech founders (Dicey Studios).

The zine also includes the other end of the platform spectrum, populated by the masses of gig workers. The contributions document the emerging forms of struggle in the food delivery sector (Jamie Woodcock), alert us of the way in which artistic critique of precarious labor can easily turn into a new entrepreneurial idea (Max Dovey); tell Her-esque tales of love between a gig worker and her monitoring app (Alina Lupu).

Some contributions deal with the impact of technology on work, in particular they look at the increasing capacity to monitor, quantify and enhance workers' activities, be they physical, cognitive, or even emotional (Phoebe Moore); they design new products and sevices to open up alternative futures and speculate about their consequences (Nefula). Precarious conditions and the entrepreneurial attempts to improve them also affect space, be that at the level of home or the city. So, we read about architects who rent their house via AirBnB while living in their studio (Lucia Dossin) and of buildings whose function is as precarious as the freelancers who inhabit them (Giacomo Boffo).

The zine also investigates the meaning and the role of the artist in an increasingly destabilized social context. The romantic image of the fully autonomous artist working in their studio is here challenged, especially in a moment when its premise of independence is being extended to the working population at large (Martine Folkersma). While the worker starts behaving like an artist, the artist is in turn pushed to outsource all the facets of their practice, thus behaving as a manager or an entrepreneur (Anxious to Make).

In conclusion, the zine calls attention to means of breaking the spell of entrepreneurialism, such as a series of videogames about the dullness and dystopian character of contemporary digital and entrepreneurial labor (Gui Machiavelli); a deconstruction of the 'tyranny of methods' of pervasive optimization techniques (Michael Dieter); and finally, a proposal for collectivized counterbehavior in place of economically exploitable behavioral coherence (Lídia Pereira).

Contributions by:

François Girard-Meunier, Katriona Beales, Evening Class, Phil N/A, Juliette Cezzar, Dicey Studios, eeefff, Olivier Fournout, Priya Prabhakar, Melissa Mesku, Jamie Woodcock, Max Dovey, Alina Lupu, Phoebe Moore, Nefula, Giacomo Boffo, Lucia Dossin, Martine Folkersma, Anxious to Make, Gui Machiavelli, Michael Dieter, Lídia Pereira

All contributions to the zine, unless otherwise specified, are licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License 1.32.

1: Pervasive Labour Union #10 - Immateriality

2: https://www.gnu.org/licenses/fdl-1.3.en.html