In The Founder, a self-described dystopian business simulator created by Francis Tseng in 2017, the player is put in the place of a nameless entrepreneur, the embodiment of “disruptive innovation.” The game’s Founder starts working in their living room and focussing on either IT or Hardware, eventually hiring employees, expanding into new locations (London, Antarctica, Bangalore, Lagos) and industries (entertainment, military, space engineering), researching new technologies, lobbying for changes in legislation and, most of all, keeping profits growing at a steady rate of 12% per year.

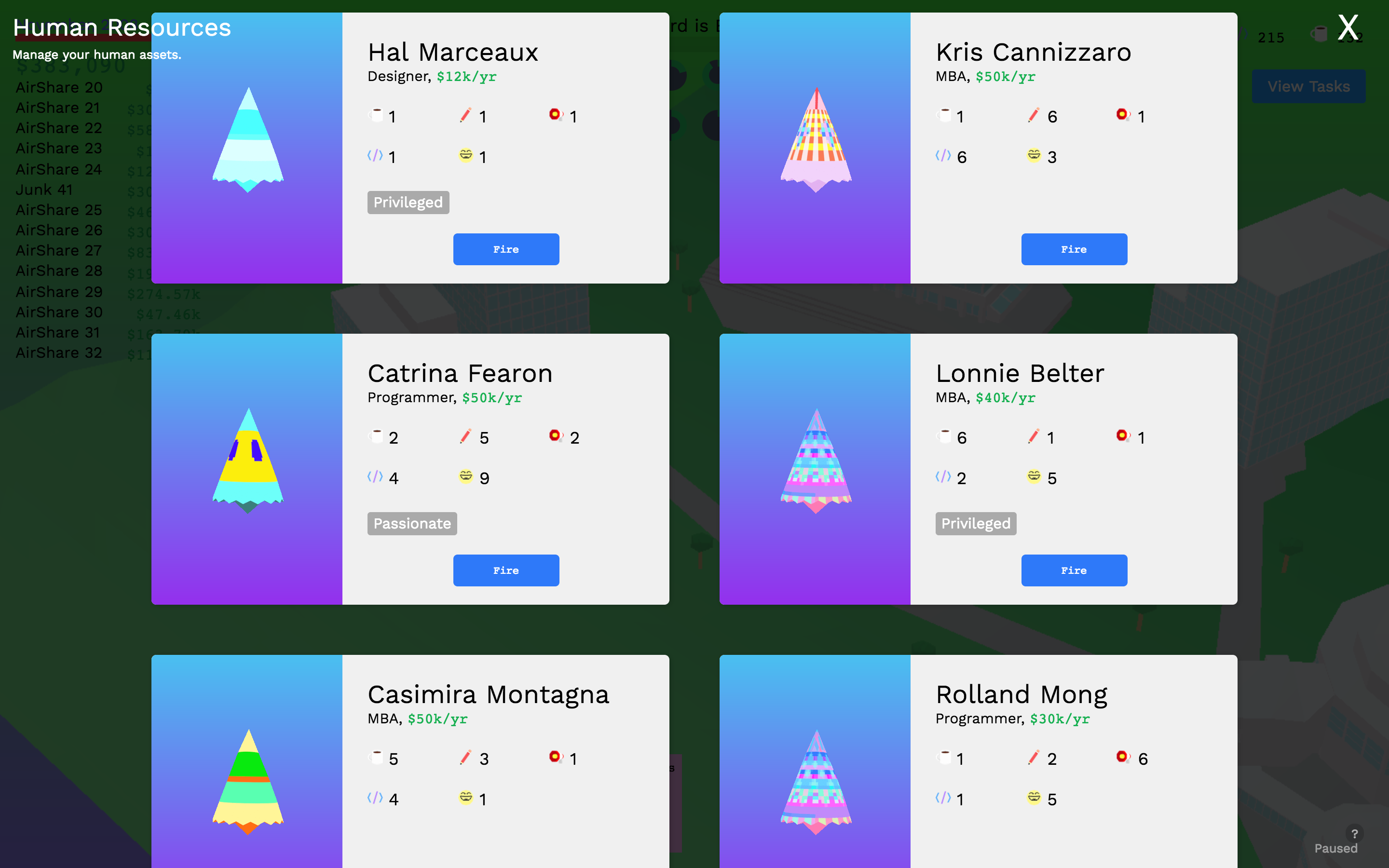

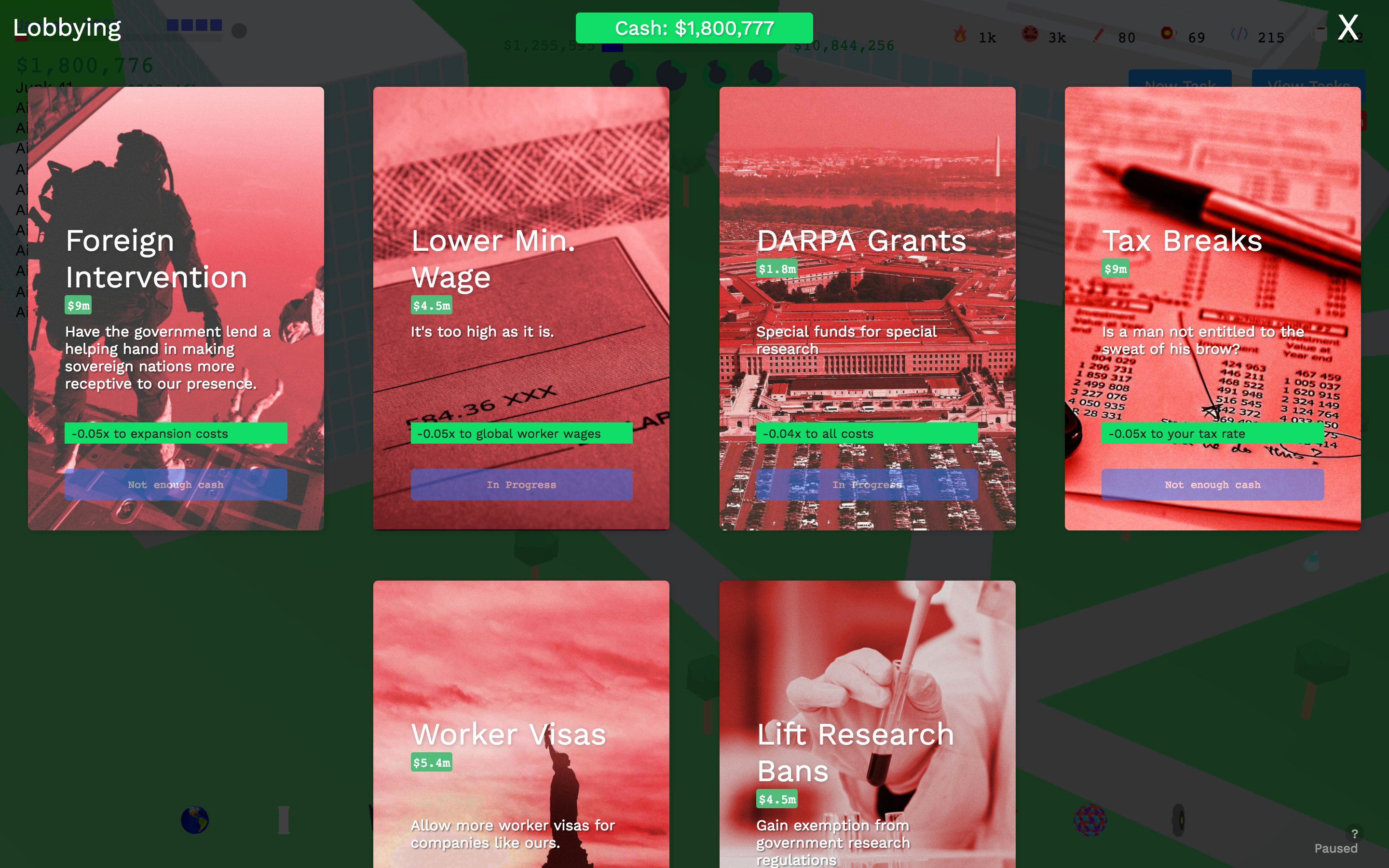

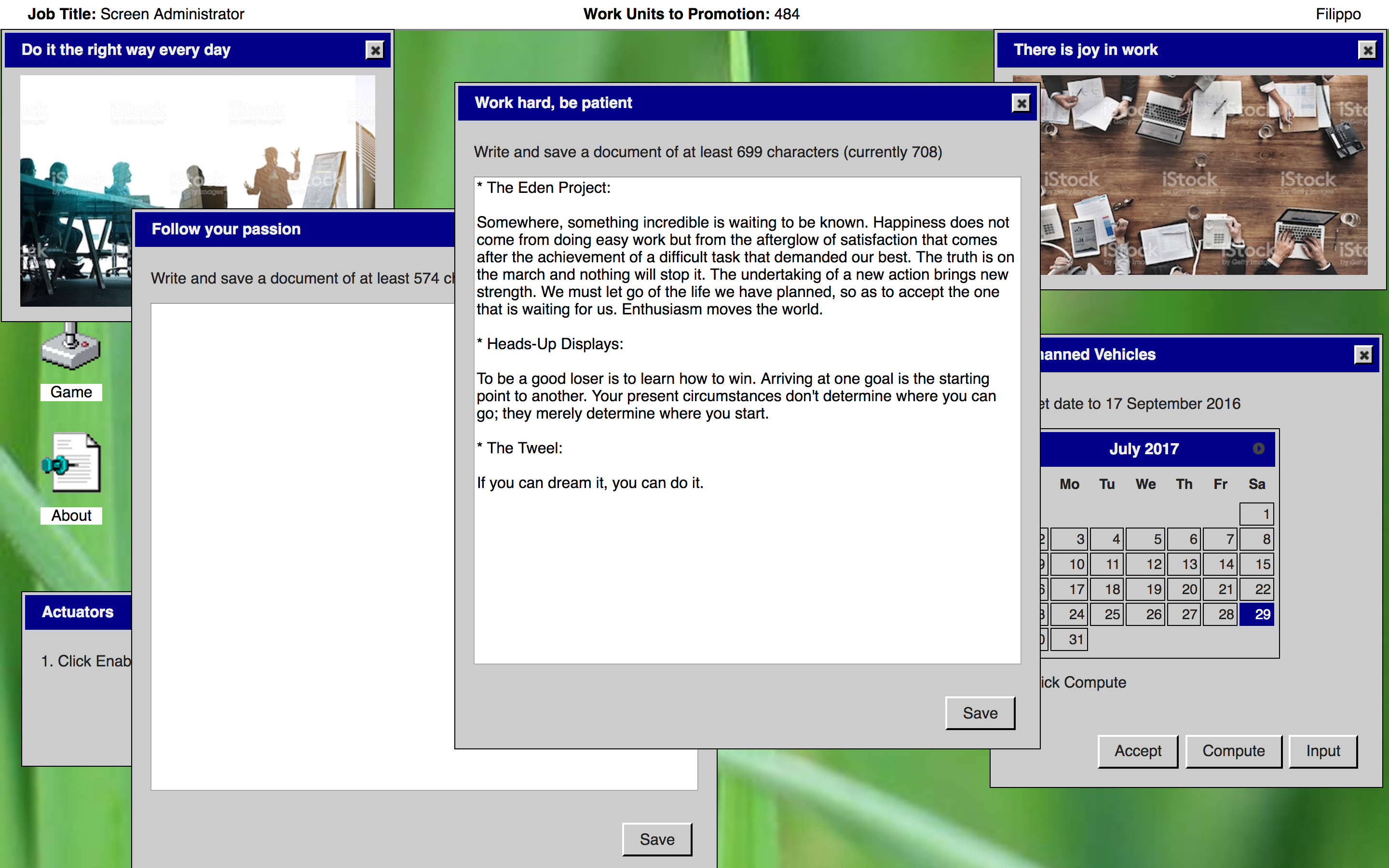

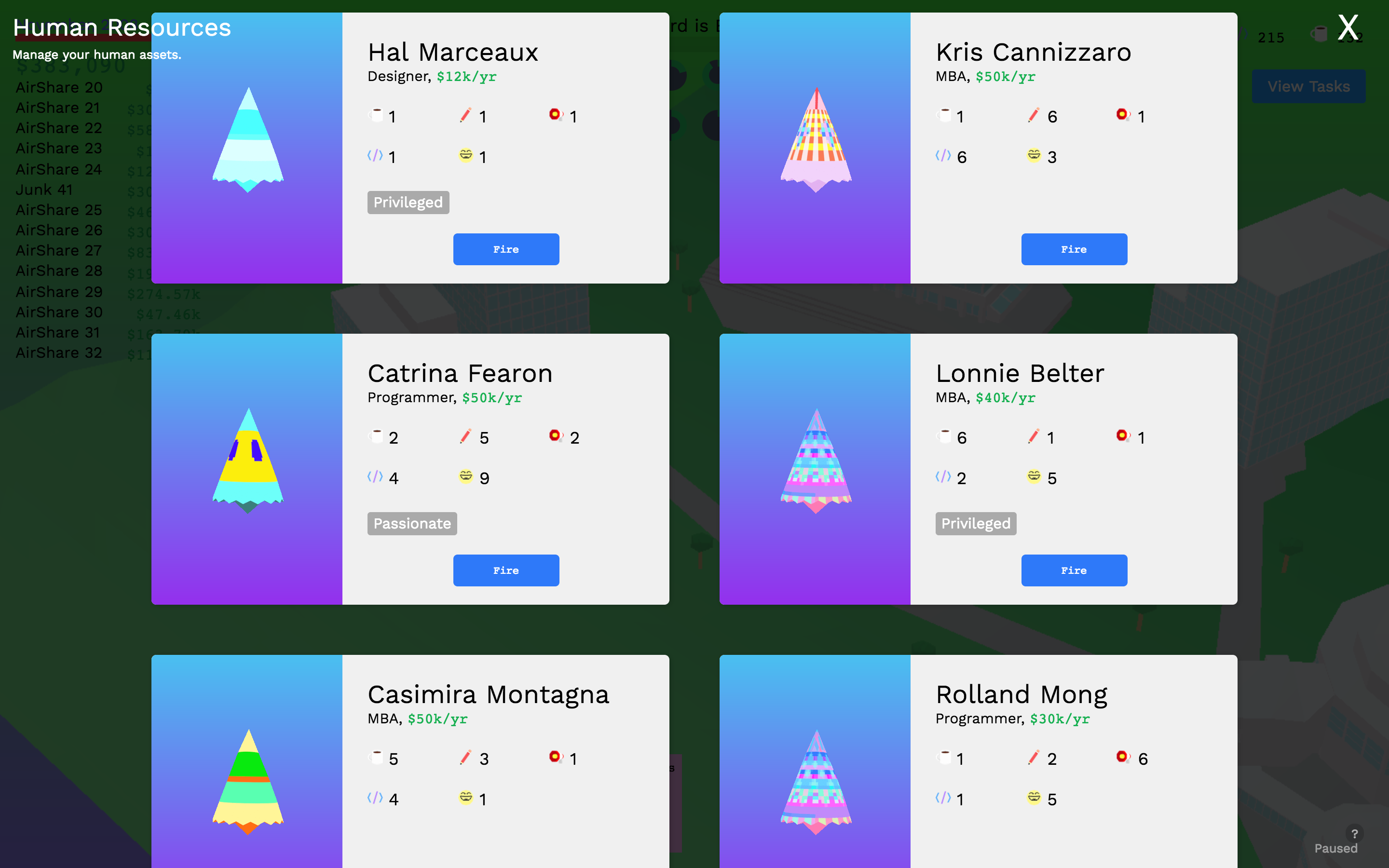

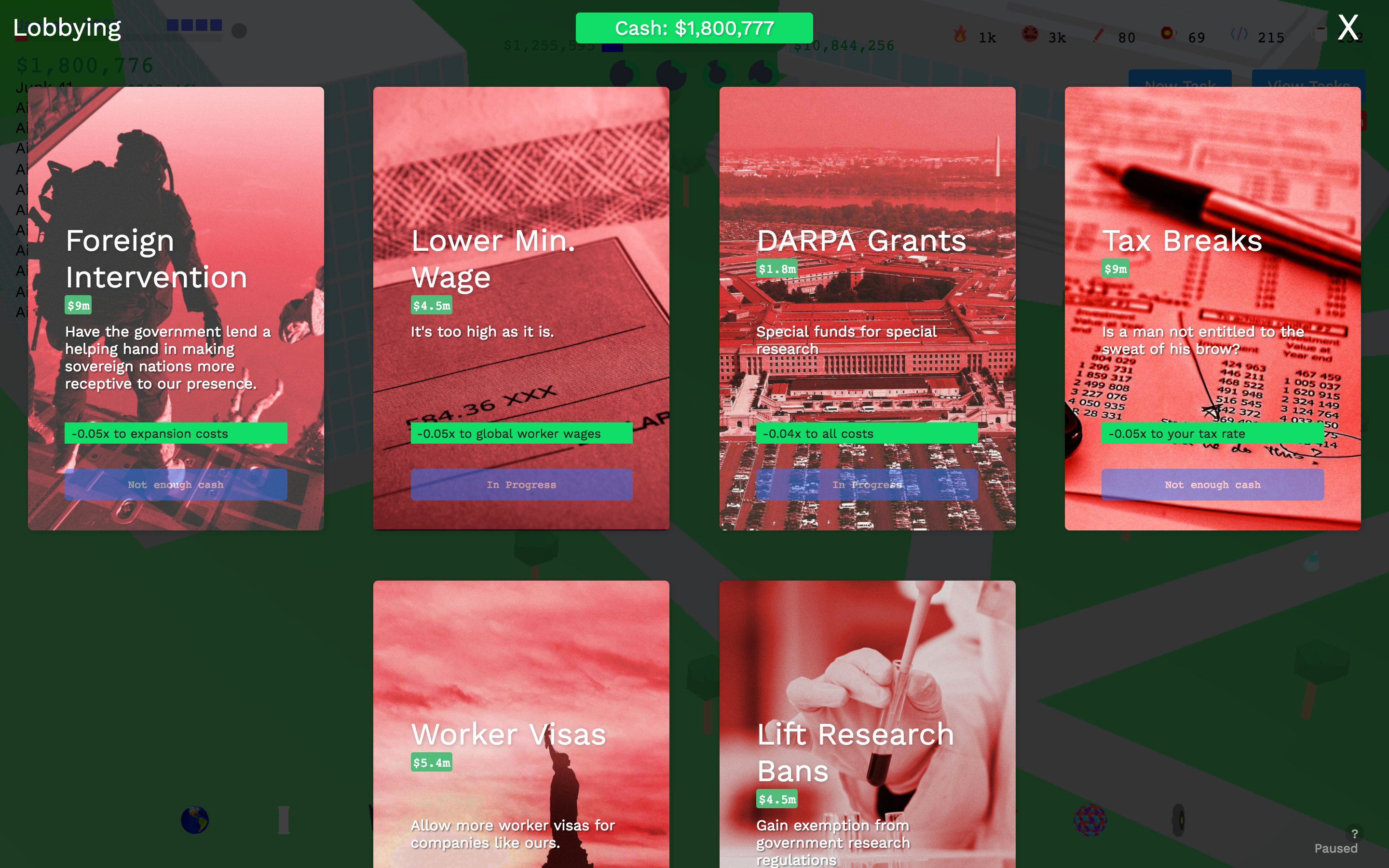

As the Founder themself, the player seeks passionate employees to join their startup: people who share the Founder’s love for innovation (though of course not a fair share of the profits) and who are excited to start working despite lower-than-average salaries. In exchange for talent and passion, the Founder offers not only silly perks (beer kegs! Catering! Always online psychologists!), but also a narrative of what the company is about, influenced by data collected from the candidate’s usage of the Founder’s social networks: “We care about the workplace culture” in case the candidate is a social person; “We are focussed on making the best products” if they are product-driven; “We are going to be huge” if they are ambitious. Candidates might still turn down an offer if it is too low, but it is not usually a cause for concern: there’s always others who, because of either passion or privilege, will be more open to edulcorated lacklustre offers. In one of my play sessions, I did struggle with finding good enough engineers and designers to accept my low salaries; after finally getting some to join my company, I immediately allocated them to lobbying with the US government for a reduction of the minimum wage. Nipping it in the bud, so to speak.

The Founder paints the cult of the entrepreneur in its most perverse undertones. Though I started out trying to give my employees a fair wage, the constant pressure from my investors quickly deprecated any ideals I might have had. As things became ever more difficult and the spectre of defeat loomed ever closer, I sacrificed my employees: I fired my tireless co-founder because he was taking studio space that could easily be filled with someone more skilled. I overworked my engineers whilst offering more meaningless trinkets and perks in return. All in the name of keeping the investors happy with their 12% annual increase in profits. By actively making these decisions, I experienced some of the mechanisms that forced this reality into being. I hounded the best “talent” and enticed it with promises of passion and relevance, only to command them to churn out mindless gadgets and services for a quick buck. What The Founder succeeds in doing is showing that, in the entrepreneurial world, passion and creativity are a thin coat of veneer applied over the actual goal of creating value for shareholders no matter what, an absurd marathon towards eternal growth that sacrifices all that is human for profit.

Though a first reading might treat the game as a warning about entrepreneurism leading us to a future dystopia if left unchecked, I’m inclined to see it differently. There is no catastrophic moment when this dystopia happens: no watershed, no sudden installation of authoritarianism, no profound change in society or its inner workings. Rather, the cataclysm of The Founder is a process of imperceptible unravelling, a slow dystopia that is already well underway — it is not a change of the status quo, it is the status quo. What The Founder tells me is not that if we keep going in this direction there will be dire consequences: it tells me that the dire consequences are already here and that we are all responsible, albeit somnambulant actors in its becoming.

It bears to say, however, that The Founder presents an overwhelmingly negative perspective that does not reflect entrepreneurialism in all its facets. Therein might lie the biggest weakness of the game: in all its jabs at start up culture and extrapolations of where it might lead us, The Founder might be guilty of preaching to the choir by ignoring any positive aspects of the ideology it attacks. I personally already believe that the start up culture is deeply flawed and worrying, but to say it is completely without its merits defies reason, especially when it is still an ideology that attracts many reasonable and well-informed people. Will an actual entrepreneur feel inclined to appreciate the insightful social commentary of a game that portrays them as evil-overlords-to-be? By denying any value to entrepreneurs, the game does not make the ideology it is attacking weaker; rather, it makes its own position more vulnerable by not acknowledging that there might still be lessons to be learned and patterns to reproduce in an effort to overcome the hold that entrepreneurialism has on western societies.

Tseng states that he wants the player to eventually realise that the world built by the Founder is not a world where anyone would want to live in. While the game no doubt succeeds in that, I believe it also does a pretty good job at showing how this world right now, when seen from the outside and from a particularly bleak perspective, is already a world where no one would want to live in. As Tseng also says, the only way to win this entrepreneurial game — to interrupt the very real dystopia we live in — is to stop playing it altogether.